Every year I post an article that lists last-minute things you can do to help your dog who is afraid of fireworks. We are coming up on Independence Day and Canada Day, and that means bangs and booms. Over the years, I have tweaked my list.

But here is an earlier reminder with the most important tip of all.

See your vet about medications (or speak to clinic staff by text or phone if that is an option).

“There are new products on the market, as well as several options that have been around for years. Here is what Dr. Lynn Honeckman, veterinary behavior resident, says about the benefits of medications.

Now is the perfect time to add an anti-anxiety medication to your firework-preparation kit. The right medication will help your pet remain calm while not causing significant sedation. It is important to practice trials of medication before the actual holiday so the effect can be properly tested.

There are a variety of medications or combinations that your veterinarian might prescribe. Medications such as Sileo, clonidine, alprazolam, gabapentin, or trazodone are the best to try due to their quick onset of action (typically within an hour) and short duration of effect (4–6 hours).

Medications such as acepromazine should be avoided as they provide sedation without the anti-anxiety effect, and could potentially cause an increase in fear.

Pets who suffer severe fear may need a combination of medications to achieve the appropriate effect, and doses may need to be increased or decreased during the trial phase. Ultimately, there is no reason to allow a pet to suffer from noise phobia. Now is the perfect time to talk with your veterinarian.”

Dr. Lynn Honeckman

I’m writing this year with a new urgency. Although I’ve had a clinically sound phobic dog before, Lewis is my first dog to have clinical thunder and fireworks phobia. We are going through that now, and I hate to think how much more affected his life would be without medications. The meds have a direct positive effect and also help make counterconditioning possible.

Sound phobia is a serious medical condition that usually gets worse. Nothing else comes close to the efficacy of medications. The research on music, pressure garments, and supplements shows weak effects at best. There is no dog crate or ear protection that can prevent your dog from hearing the low-frequency bangs and booms. The best way to help your dog get through the coming holidays in the U.S. and Canada is to contact your vet for help. Call now.

Bonus Tip: There Is New Evidence to Support Ad Hoc Counterconditioning

I plan to publish a whole post on this topic, but I haven’t done it yet. I do recommend ad hoc counterconditioning in my other post, and in recent years there has been evidence of its efficacy.

Ad hoc counterconditioning is counterconditioning without desensitization. It’s the practice of providing appetitive stimuli (usually food or play) after the occurrence of the trigger. In other word: drop great food whenever fireworks go off. But also, feel free to treat for other sudden sounds: door slams, objects dropping on the floor, something popping—any impulse sound.

Dr. Stefanie Riemer has published three papers in the last few years on fireworks fears in dogs. Her bio states:

I am a behavioural biologist and am especially interested in how dogs feel and think. My research interests include emotional expression and social communication in dogs, personality development, noise fears and veterinary fear in dogs as well as the phenomenon of so-called ‘ball junkies’ and possible parallels with behavioural addictions in humans.

Her research is fascinating, and her papers are very readable and available ungated online. Here’s where to check them out.

Her research also supports the use of anxiolytic medication, so we come full circle to Dr. Honeckman’s words: now is a great time to talk to your veterinarian. And if you can, be ready to drop treats—good ones!

Copyright 2019 Eileen Anderson, edited 2024

Related Post

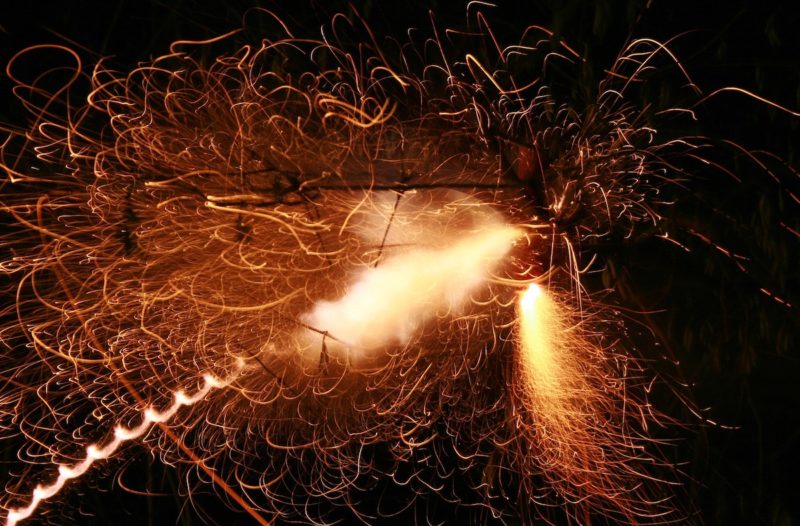

Photo Credits

- Two photos of Zani copyright Eileen Anderson.

- Firecrackers courtesy of Wikimedia Commons from user Tom Harpel, under this license. I cropped the photo and edited out some background items.